images: Marvel

by Rich Kirby

When movie ticket service Fandango announced that Black Panther had set a box office pre-sale record among the Marvel Cinematic Universe of films, even the few holdout superhero haters had to take notice. All this came as no surprise in the Twitterverse, which made the movie the ninth most tweeted about feature film of 2017 – even though it was not scheduled to release until February of 2018.

There’s been a lot to tweet about. Chadwick Boseman’s portrayal of Black Panther in his movie debut was the surprise hit of Captain America: Civil War. The new movie’s cast of ‘A’-listers includes Michael B. Jordan, Forest Whitaker, Angela Bassett, and fan-favorite Danai Gurira from TV’s The Walking Dead. The plot plays out mostly in Africa, and over ninety percent of the cast are black actors. (This bodes well for Hollywood’s commitment to diversity, but less so for that Stan Lee cameo; our fingers are crossed.)

But what of His Highness, himself? King T’Challa has had multiple comics series and has been an Avenger in the Marvel Comics universe (although so were Jack Of Hearts and 3-D Man, so the bar’s not really all that high). Yet outside of some feel-good but heavy-handed social justice warrior-ing against Klansmen in the American South and Apartheid in South Africa, reasonable men and comics fans can argue the Wakandan king’s been a bit under-utilized.

The character garnered more than a little buzz when he was first introduced, not surprising given the evening news at the time. Marvel gets to call “dibs” on Black Panther, as they debuted their fictional king and superhero in the comics in July 1966, three months earlier than the more famous revolutionary socialist party of the same name. Both regent and radicals were birthed at the height of the country’s civil rights movement. As first conceived by creative team Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, the character’s name was to be Coal Tiger, with a few costume tweaks before his premiere in Fantastic Four #52.

initial character design by Jack Kirby

first cover (rejected) / revised published cover

Although a sensation at the time as the first superhero of clear African descent, Black Panther was not mainstream comics’ first hero of color. That distinction falls to Waku, Prince of the Bantu, a sort of “Galahad of the Savannah” who debuted in Atlas Comics’ Jungle Tales anthology in 1954. The credit for being the first black comic book headliner goes to Dell Comics’ Wild West gunslinger Lobo, whose book debuted in Dec 1965 and ran for just two issues through September 1966. Marvel’s Luke Cage got his own book in 1972 (originally called Luke Cage, Hero for Hire), and the Black Panther’s own Jungle Action would follow a year later at the height of pop culture’s blaxploitation movement.

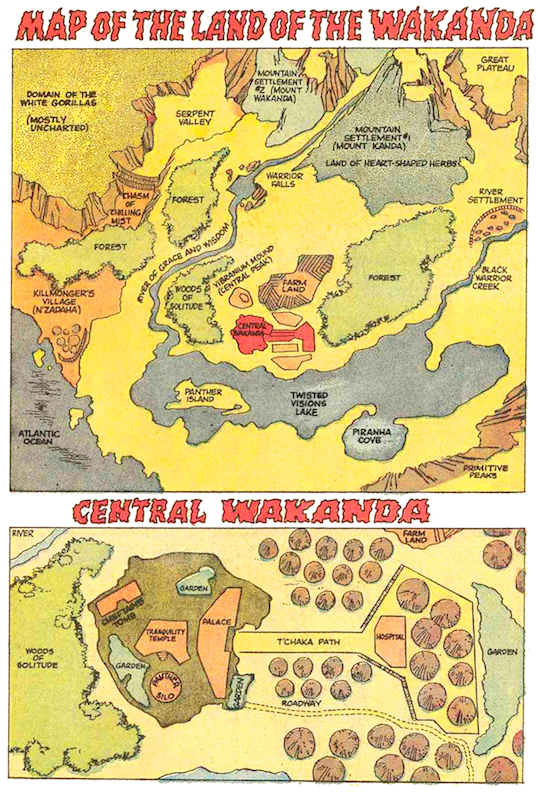

But what distinguished T’Challa from Cage and the other “urban heroes” popping up like corner thugs in the comics in the mid-70’s was the emphasis on his homeland. It was a brave and unlikely gambit for Lee and Kirby, whose audience’s main exposure to Africans had been the steppin’ and fetchin’ extras in need of saving by Johnny Weismuller’s Tarzan.

With the Black Panther’s debut in FF #52, Lee and Kirby played to those stereotypes and then up-ended them. Wakanda was revealed to be the most technologically advanced nation on earth. Its king T’Challa possessed an intellect nearly on par with super-genius Dr. Reed Richards himself, and a net worth that surpassed even that of Tony Stark. (In the movie, the brains of the family are bequeathed to T’Challa’s sister, Princess Shuri.) Lee took one pop culture trope – the notion of Africa being exploited for its resources – and amplified it, comic book style. His Wakanda would be home to vibranium, a metal from a 10,000 year old meteor that was the rarest and most valuable resource in the world.

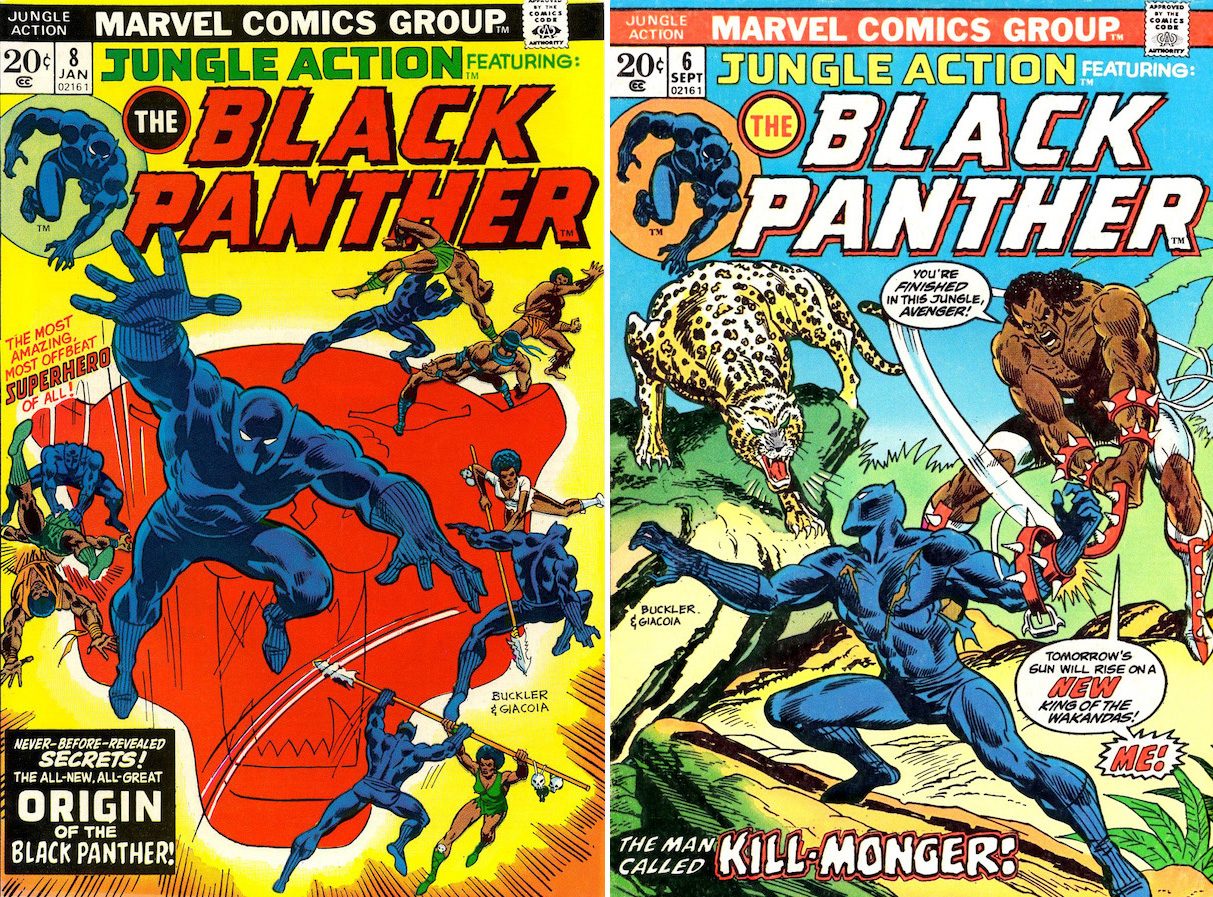

When the Black Panther got his own title in 1973 (Jungle Action featuring The Black Panther), writer Don McGregor pushed the boundaries of racial representation even further, fleshing out the Wakandan court and place in geo-politics in what would be the first real multi-book arc in comics history. And in fact, many consider the acclaimed “Panther’s Rage” story to be comics’ first graphic novel. Many of the characters and most of T’Challa’s back story as featured in the upcoming film date from McGregor’s groundbreaking run.

Christopher Priest began writing Black Panther in 1998 for the Marvel Knights imprint, a Hail Mary pass thrown in the dark days just after Marvel’s bankruptcy. The imprint featured series headlining T’Challa, Daredevil, the Punisher, and the Inhumans, all unfettered by the continuity that constrained the other more numerous, less expensive, and arguably less mature titles the House of Ideas was cranking out at the time. Priest’s 62-issue run on the series has also been mined deeply for the script of the film, particularly in the character of American government liaison Everett Ross, played by Martin Freeman.

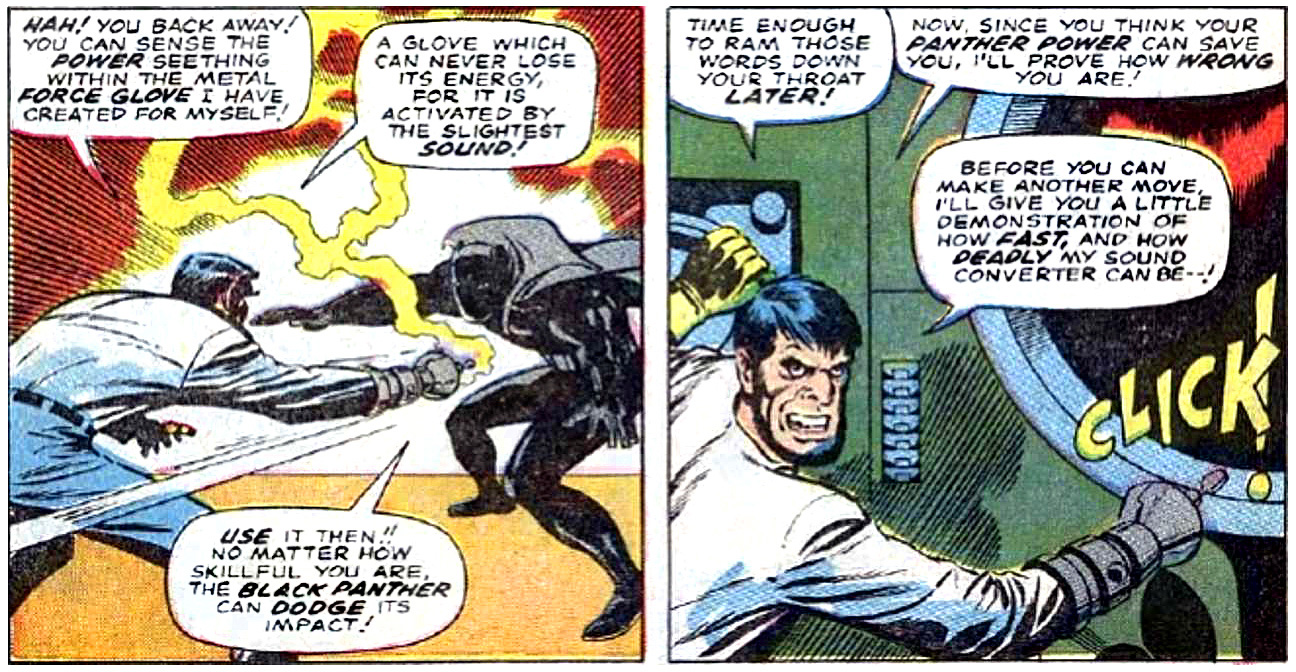

As always, you can judge a man – especially a hero – by his enemies, and Black Panther’s rogues gallery doesn’t disappoint. In the comics, T’Challa’s father is killed by vibranium thief Ulysses Klaue. After losing his hand in a fight with the hero, the villainous Klaue became the super-villainous “Klaw, Master of Sound,” his missing hand replaced by a “sonic transducer.” In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Klaue (played by genre film stalwart Andy Serkis) is an illegal weapons merchant who lost his arm to the robot antagonist in Avengers: Age of Ultron. He is set to return in Black Panther with his own weaponized prosthetic.

It wouldn’t do for a hero of Black Panther’s stature to scrap with just one nemesis in his first movie as a headliner, and Marvel Studios has obliged by adding Erik Killmonger into the mix of meanies. Killmonger (real name Erik Stevens, real name N’Jadaka) is Black Panther’s opposite number in both the comics and the film, a Wakandan native whose family was exiled by T’Challa’s father. Played in the movie by Michael B. Jordan, Killmonger trained as a black ops commando in the U.S. during his exile, and so is no slouch in the fisticuffs department.

As for super powers, the Black Panther’s creative teams have left nothing to chance. The king’s speed, agility, strength, endurance, healing and senses are enhanced to super-soldier levels due to the mystical and vibranium-drenched “heart-shaped herb” (no extra points for guessing in which country it exclusively grows).

As for super powers, the Black Panther’s creative teams have left nothing to chance. The king’s speed, agility, strength, endurance, healing and senses are enhanced to super-soldier levels due to the mystical and vibranium-drenched “heart-shaped herb” (no extra points for guessing in which country it exclusively grows).

It’s not that T’Challa needs any help in the tough guy department. You don’t get to become the warrior king of his ancient race – the Black Panther is an otherwise hereditary royal title – unless you can defeat Wakanda’s six greatest warriors in ritual combat.

And that costume! The “panther habit” is made from a vibranium weave which is both impenetrable and absorbs kinetic energy, allowing its wearer to fall great distances unharmed. As upgraded in the movie by Princess Shuri, that feature now allows the Black Panther to both store and re-direct that energy, giving the hero the ability to overturn cars if, say, enough bullets are shot at him. From what we have seen in the trailers, there are no worries on that front…

There is little question we will see an increase in T’Challa cosplay on the convention floors this summer, but we’re most excited about the possibilities swirling around the rest of the Wakandan court. The film’s costume designer, Ruth E. Carter, has infused the traditional garb of tribes such as the Maasai and the Himba with a science-fiction aesthetic that we think will net her an Oscar nomination at the very least.

Black Panther is scheduled for general release, as well as in IMAX and 3D, on February 16.